Dear everyone,

Hi! Shorter post this week because IT’S BRENTY’S BIRTHDAY AHHH meaning we’re full-sending it in La La Land feat. Catalina (yes, of the wine mixers). Here are some thoughts on Lorde’s Virgin, which was released two Fridays ago (and which, for the most part, I’ve loved, although I agree with some takes I’ve seen that it loses momentum in the second half):

Lorde is Born Again on Virgin

Lorde’s hot youth has cooled on Virgin, leaving her with mirrors of transformation. The album is an exploration of intimacy with oneself after your twenties’ frenzy. We listen as Lorde comes into her adult body, making sense of her gender expression and matriline with a raw curiosity scored by synthetic drums. “I might have been born again,” she sings on the album opener, “I’m ready to feel like I don’t have the answers.”

Virgin is a kind of second adolescence, one in which Lorde harnesses the intensity of her interiority towards sublime self-(re)discovery. If her other albums are concerned with narrative—of how to best capture her stories of coming-of-age, romance, and actualization through the specificity of song—Virgin is more interested what it means to be your own muse. Lorde’s pen transforms into a hammer: Her body and its truths are hers to chip and mold.

Super-Chill Scorpio Sisters: Lorde and Me

When Melodrama came out, I was on fire. I don’t mean I was “in the zone,” or hitting some kind of winning streak—I mean I constantly felt like my skin was aflame, that a lava-broil prickled beneath me at every hour. My days were a near-constant mix of adrenaline and discomfort, some epiphany sharp then gone again by nightfall, drained with my double vodka tonic.

During that time—summer, 2017—I lived in a college house on East Norwich in Columbus, Ohio, subletting the basement with some of the best roommates I’ve had to date (an area of my life where I’ve been tremendously lucky, tbh). My room was next to the laundry machines and it was, naturally, dim and damp, like living inside a cotton swab. Every night, I fell asleep to the smell of dryer sheets, the drum of the washer, and the stale thickness of the air. I had a slight cold that whole July.

I had graduated from Miami one month ago and found myself in a fit of post-grad restlessness; I spent the season tossing and turning, even while awake. When Lorde released her “Green Light” music video, in which she stomps across Manhattan in a deep mauve dress, I resonated with her resolve, its ferocity and aimlessness. In my ’02 Accord, I spat the lyric She thinks you love the beach, you’re such a damn liar with such venom you’d think I wrote the line (or had a personal vendetta against boys on beaches). One of my new roommates and I texted “Supercut” lyrics back-and-forth in all-caps, agreeing it spoke to our respective situations with uncanny precision: “IN MY HEAD I DO EVERYTHING RIGHT” stood bubbled in blue, speaking for itself. “WHEN YOU CALL I FORGIVE AND NOT FIGHT.” Two months later, I lived in Chicago, and when I looked out the El window, I listened to “Writer in the Dark” like a prayer, hoping the seasons might change my mind.

Lorde was born exactly 364 days after me—November 7, 1996 (And, like me, she suffers from the quintessentially Scorpio affliction of taking yourself too seriously). When, at sixteen, her song “Royals” (2013) anointed her an indie-pop wunderkind, she felt like a gifted peer. As a high school senior, I too, was driving around suburbs and drinking on tennis courts; I didn’t write an album about it, of course, but that mundanity felt of opus-import—I wondered: Was nothing happening, or everything? How do you know when your life has really, actually begun?

Nearly every interview or review of Lorde during that time hailed her wisdom for her age. An artist “beyond her years,” her sagacity lied in her ability to make the unspectacular glimmer and snap. “We live in cities, you’ll never see on screen,” she famously snarled. “Not very pretty, but we sure know how to run things.”

By Melodrama, Lorde and I had both lived enough to have regrets, but our youth was fresh enough for them to feel novel, or maybe even reversible, if we could play a night-out’s cards just right. By Solar Power, we sought wellness, were desperate for bliss, even if we didn’t quite know how to go about either.

All this to say…. I feel like I really get where Lorde’s at on Virgin. Before her recent album’s title was officially announced, there were rumors that it would be called “After the ecstasy, the laundry,” a reference to a book on spiritual enlightenment by Jack Kornfield. On Virgin standout, “Clearblue,” Lorde sings a new version of the line: “After the ecstasy, testing for pregnancy.” This line details a particular scene in the singer’s life: That strange confrontation with plastic and biology as the past-due-period days accumulate, when you misinterpret every sensation with the hope of that red safety signal. Yet, it also concisely represents the themes of Virgin—after the ecstasy, aka the just-post-adolescent fervor of Melodrama, testing for pregnancy, aka the possibility for parenthood suddenly available. The line gestures at one of the grander questions that tugs at Virgin: What comes after youth and before maturity? When you’re not quite the wise woman you dreamed you would be, but you can no longer convincingly cast yourself as the ingenue? Who are you when you’re no longer the maiden, but not quite the queen?

Virgin starts with “Hammer” and ends with “David,” a reference to the iconic sculpture. If Lorde is wielding a hammer, as I suggested above, she’s chipping away at “David” on her own accord. Here, Lorde recasts her relationship as an artist with a muse: Whereas, on Melodrama’s “The Louvre” she professed that her and lover belong among the greats of Western art (“Down the back, but who cares…. Still the Louvre”), on Virgin, it is her perspective that makes something art—or, rather, she intimates that her perception is art itself. She is no longer concerned with the narrative of her romance, how it appears externally, but is interested in the “nails” she seeks, the ways in which she sculpts and constructs her own life.

Much of Virgin is about sex, its specific—even gnarly—textures. Yet, even in scenes of intimacy with a partner, the focus is on Lorde: Her need to be touched, still, after everything. Virgin is interested in perception that doesn’t feel like consumption, but being seen. On “Hammer,” Lorde gets an aura picture taken, hoping it shows her who she is. She watches Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee’s sex tape on “Current Affairs,” muses that “it was pure and true,” before the film “came out.” Anderson and Lee meant for the tape to be private, and its leak is a violation; even while Lorde finds beauty in it, she wonders about the ethics of pursuing pleasure. “Would you dive to the ocean floor / Just to take my pearl?” she sings a line later, which I read as both an inquiry into her lover’s endurance and a wariness of capture—the diver travels fathoms to “take” something precious, private, and sacred: That can be real intimacy or cruel seizure, depending on the context of consent.

On “Man of the Year,” Lorde becomes her own lover. She breaks herself open in a way no one else could. When she sings “Some days I’m a woman / Some days I’m a man,” that is a declaration for herself, a firm and indisputable account of how it really feels to be in her own body, at last. On an album standout, “Shapeshifter,” Lorde reflects on her objectification, how she has played endless roles as a woman and had them cast for her:

I’ve been the ice, I’ve been the flame

I’ve been the prize, the ball, the chain

I’ve been the dice, the magic eight

So I’m not affected

I’ve been the siren, been the saint

I’ve been the fruit that leaves a stain

I’ve been up on the pedestal

But tonight I just wanna fall

That “fall” is a reprieve from shapeshifting for others’ gazes, from being contained to the pedestal. Lorde cycles through archetypes of womanhood—the siren, the saint, a fruit-eating Eve—and ultimately claims her desire to discard them. This desire crystallizes again on “Broken Glass,” a song that chronicles Lorde’s relationship with disordered eating; She wants to shatter the glass of her appearance, her obsession with and punishing of her frame. She worries that smashing might be “years of bad luck,” before ruminating that it might “just be broken glass.” What if, instead of constantly searching and assigning narrative value to ourselves, we took things as they are—broken glass as simple shards, a pedestal fallen, a body, alive and moving?

What comes after youth and before maturity? Motherhood is another theme on Virgin, where Lorde repeatedly performs for hers, seeking approval (particularly on “Favorite Daughter”).

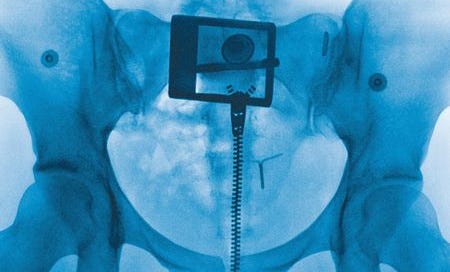

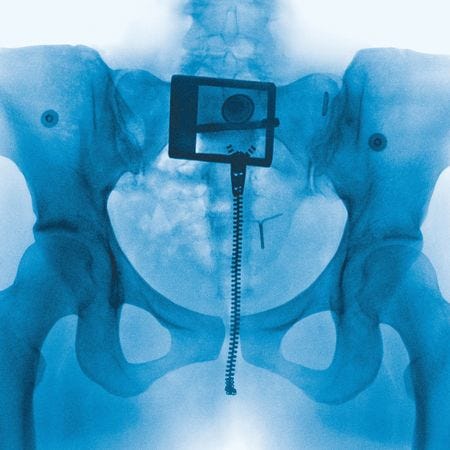

Listening to Lorde call on her mother, I thought of mine, how she was 27 when she had me, an age that I am now two years past. Some days I wonder if I am behind on growing up, but most days I feel stunned with gratitude that I get to do so many things at 29—to have lived and travelled to so many cities, to have had years devoted expressly to finding myself and my voice—that, perhaps, my own mother would not have dared dream of. The Virgin cover is an X-ray of Lorde’s pelvis, displaying her IUD, by photographer Heji Shin, who is best known for her images of crowning newborns. The cover suggests creativity as a kind of pregnancy; Lorde is giving birth to herself. Maybe that’s what this time of life is all about.

As I write this, I am on a plane en route to my best friend’s birthday. A young boy falls asleep on his mother’s lap and she absentmindedly combs his gold hair with her fingers. She’s sipping complimentary coffee and watching Crazy Rich Asians (aka the plane movie). If that is my destiny—and I hope it is—I should savor this: This sitting alone, my fingers on the keyboard as if I am sticking my hands inside a magic shoebox, feeling around for whatever comes out and hoping it comes true. Space to search within myself as I fly to the people I love. Between youth and maturity, maiden and mother, and naivety and wisdom, there’s an intimacy with the self, a coming into your body and all it’s been through thus far that it’s irreplaceable. That trust can be the amulet you take with you as you ripen and age—yes, it took time, and it’ll take some more. That’s the gift of getting to begin, to be born, again and again.

One Nightstand:

- I finished Matryr! And it was truly transcendent. So powerful and beautifully written. Will maybe write a lengthier post about it in the future, but for now, I’m still thinking about these two sentences: “An alphabet, like a life, is a finite set of shapes. With it one can produce almost anything.” And: “Love was a room that appeared when you stepped into it. Cyrus understood that now, and stepped.”

- It’s officially full-on summer, which means two things: I’m doing my annual SATC rewatch and reading Elena Ferrante. Started The Days of Abandonment (only one of hers I haven’t read) in-flight, and ofc, loving it so far.

- Being w/ Brenty (and Ri! And Poki!) for the birthweek means my nightstands look, gloriously, something like this rn:

Prompt of the Week:

What is your ultimate song of the summer? Like which track just takes you BACK to the specific summer.

Love,

Jen