Hi everyone,

Hope you’re well—this dog-days time of year always reminds me of two of my favorite pieces of music: Lana Del Rey’s Normal Fucking Rockwell! (probably my favorite album of all time), and Phoebe Bridgers’s cover of Summer’s End (originally by John Prine).

^ There aren’t many lyrics that soothe me more than: “In your car / the windows are wide open.”

A piece of exciting news: Time Being Books, one of my favorite places in Austin (run by my amazing and generous friend, Addie Oscher!), is featuring my article, “‘In Pieces’: Nina Simone’s Critical Geographies and Listening as Incommensurable Practice,” as part of their “Research in Practice” series. “In Pieces” is an excerpt from the first chapter of my dissertation. I’m thrilled that Time Being is making it more accessible—truly a model for how resource sharing should be <3

My SubStack article for this week is a bit of a departure from my usual fare. I wanted to write about envy and whether it can possible be a generative emotions: One that unites and teaches, rather than divides and distorts. Let’s get into it.

Can envy be a generative emotion?

“Thou shalt not covet,” the Bible warns; “envy is pain at the fortune of others,” Aristotle writes.

Oh, envy. The word itself summons to mind depraved witches and petty stepsisters, desperate to thwart some maiden’s radiant destiny. As an emotion, envy is considered to be so undesirable, so gruesome, that it’s literally equated with monstrosity.

But is it possible that enviousness—in all its green-eyed grotesquerie—can be generative? Can envy ever deepen relationships instead of wedging them apart?

Emotions researcher, Brené Brown—who is best known for her viral TEDx talks on vulnerability and shame—defines envy and jealousy as two related, yet distinct, feelings. “Envy,” she shares, “occurs when we want something that another person has.” Meanwhile, “jealousy is when we fear losing a relationship or a valued part of a relationship that we already have.” You might be envious of a friend’s professional achievements, access to community, or romantic relationship, but you would be jealous of a friend spending more time with their shiny-new acquaintance. I’ll talk about both emotions in this article, but will focus more explicitly on envy.

^ One of Brown’s popular TEDx talks. Highly recommend her book and HBO series, Atlas of the Heart, where she writes about envy and other emotions!

Brown hypothesizes that, as a culture, we use the term “envious” less than “jealous” because envy is associated with hostility (“Envy”’s distinction as one of the seven deadly sins isn’t great PR, either). Although “envy” may come with a greater stigma than jealousy, both emotions are viewed as childish and unbecoming: There’s a reason that “they’re just jealous” is usually offered as a consolation to victims of school-age bullies.

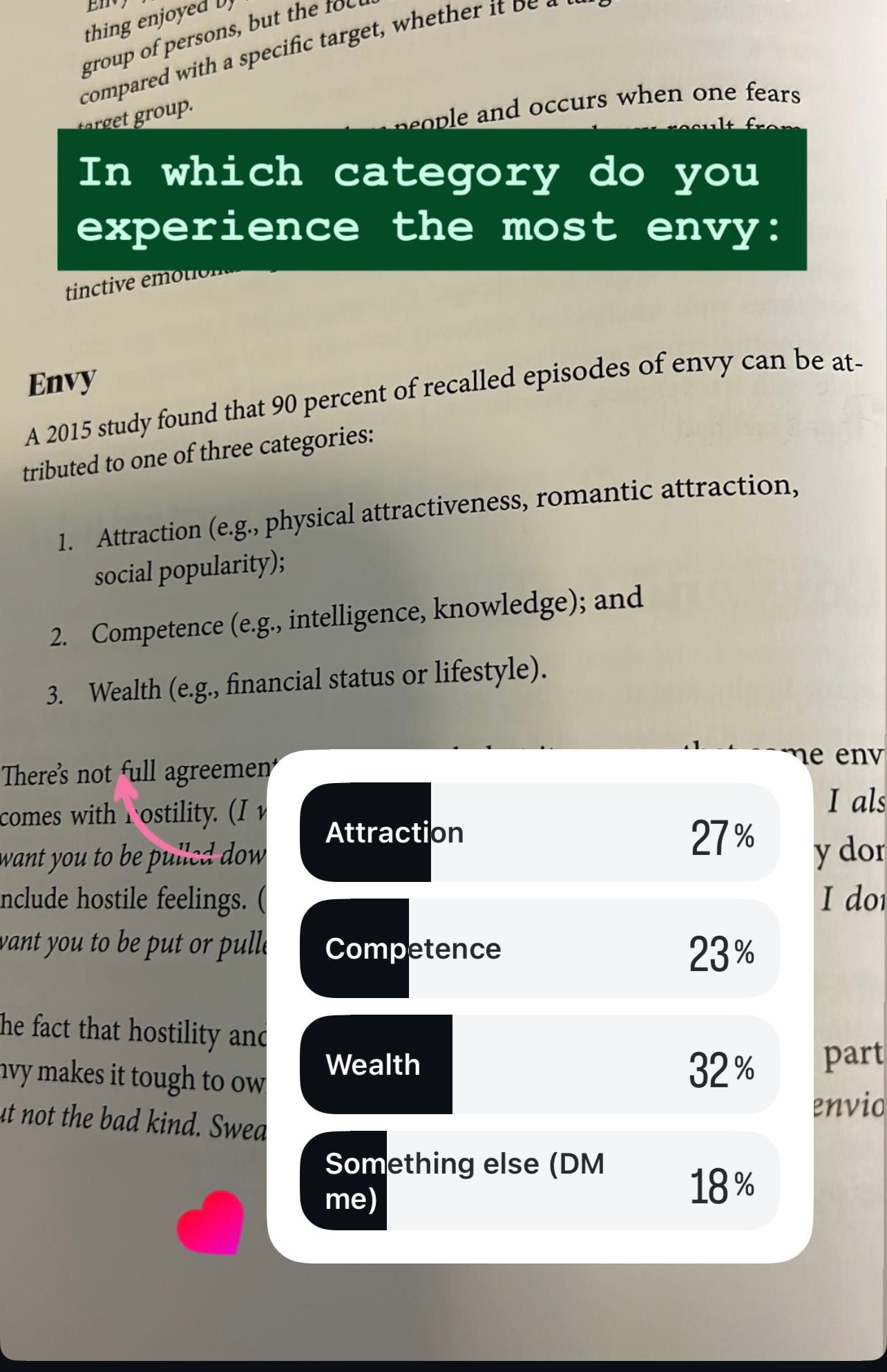

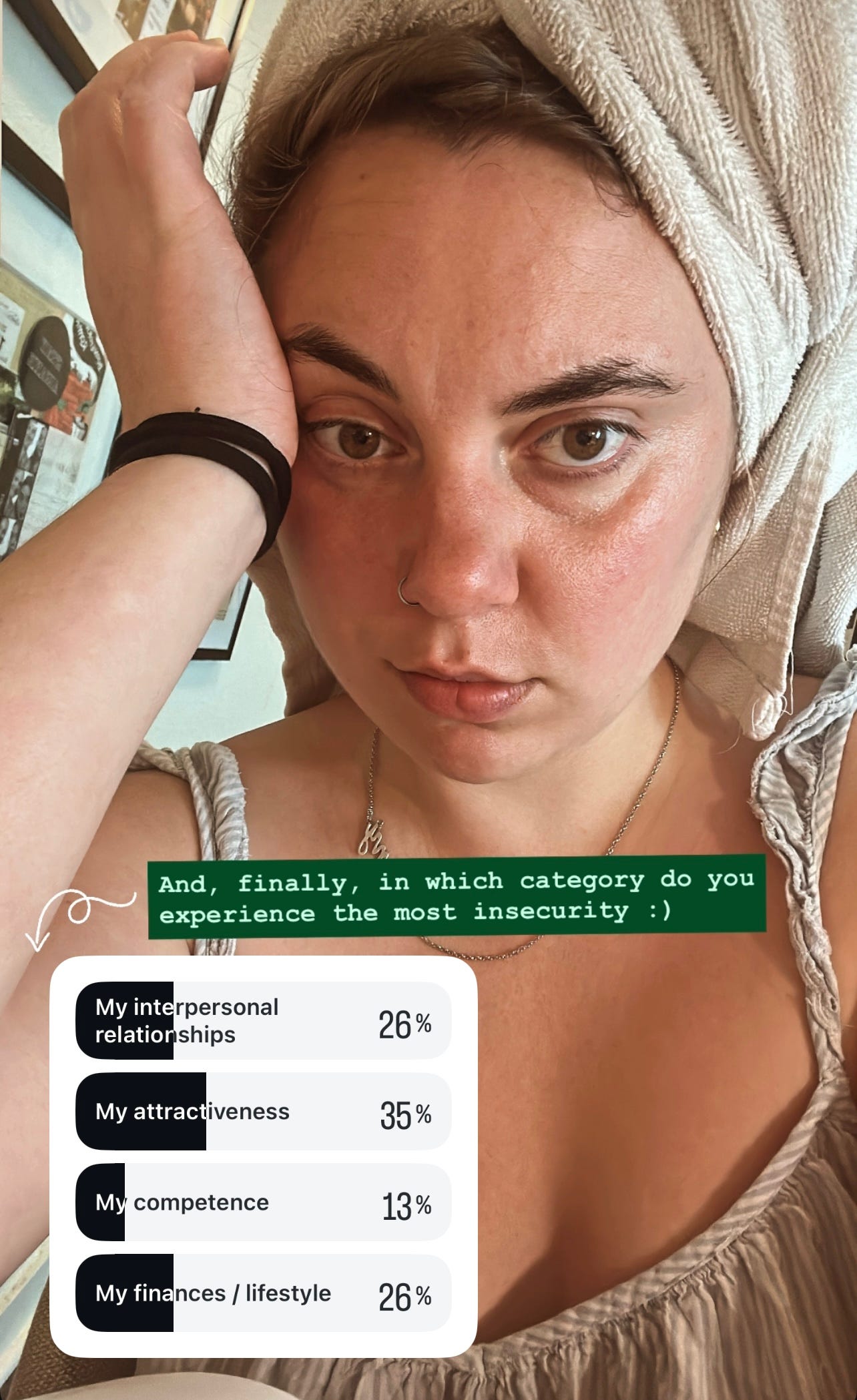

I’d argue that nearly all of us are experiencing envy and jealousy far more frequently and acutely than is socially acceptable for us to articulate. In preparation for this essay, I posted a few questions about both emotions to my Instagram; the responses that I received were enthusiastic and relieved. Chatting back and forth with many of you, it became clear to me that most of us yearn to talk about envy and jealousy without shame. We want to unburden ourselves from the all-consuming comparison narratives that plague us—that are woven inside of some of our closest relationships—without our comments seeming like an attack (Even in writing this, I’ve deleted so many specific examples of envy from my own life; it feels impossible to write about surface-level envy in a way that testifies to just how layered the situation is, that does justice to all parties and factors).

Envy is also an emotion we’ve likely been on the other side of, which I’ll talk about in a bit. I hate that feeling, too, and have experienced so much guilt and sadness from it. I can’t help but wonder: Is there a way to talk about envy without it becoming an indictment or—maybe even worse—a one-way pity party?

Where does envy come from?

I have found that primal, yell-in-your-pillow sort of envy almost always boils down one of two beliefs: They don’t deserve it; or I can never have it.

Each of these stories is harmful and limiting to both parties. And sometimes the second reason—“I can never have it”—disguises itself as the first, the bite of resentment a cloak for private insecurity.

Envy is instructive, or so the therapeutic adage goes, because it reveals what we really want. But what’s the line between need and entitlement? And when you are in the plunges of precarity, how do you decipher between real and imagined lack?

When I look honestly at my catalogue of envies, it might as well be a list, pinched deep in my heart, of my greatest insecurities. Although “green-eyed,” as in envious, and being “green,” as in inexperienced, derive from different contexts, their shared verdigris gestures to both states’ sensitive nature. To be envious is to be made vulnerable—to admit to an aspect of your inner world that is as delicate and tepid as a fledgling sprout. No wonder we’re so quick to cover our envies with scorn: We’re protecting the frailest sides of ourselves!

In popular culture, we don’t have many models for healthy expressions of envy. Fairy tales are laden with wicked allegories of envy and its consequences: Most obviously, The Evil Queen desires Snow White’s youthful beauty so much that she plots to murder her. Mirror, mirror, on the wall, the Queen obsessively chants, Who’s the fairest of them all? When the magic mirror spites its proprietor’s vanity and selects her stepdaughter as the kingdom’s fairest, the Queen is driven mad with envy. She sends her huntsman to kill Snow White and, as proof of his conquest, bring back her human heart, encased in a bejeweled box.

^ Poster child for envy.

In the original Brothers Grimm story, the Queen orders the huntsman to return with not Snow White’s heart, but her lungs and liver. Why? Because the Queen plans to have the princess’s organs boiled and salted, so that she can eat them.

As cannibalistic as this depraved little detail is (wonder why they omitted it from the Disney version!!), I find that it encapsulates the grittiness—the visceral, blood-and-guts quality—of true envy better than the Evil Queen’s impervious gazing into her magical mirror does. Like all of our grandest emotions—the ones that are so all-consuming they have entire literary genres and branches of Freudian psychology devoted to exploring them—envy is not logical. It is embodied; it cuts deep. There’s a reason why, when Olivia Rodrigo snarl-sings “All I see is what I should be / Prettier / happier / jealousy / jealousy,” every note sounds like an ax-sharpened dagger.

^ Honestly a good model for expressing jealousy with nuance.

Antidotes for envy, and moving beyond the “they’re just jealous” story

As unpleasant as envy feels, being on its receiving end is also pretty freaking awful. You wonder: Has this person been secretly filing evidence against me this whole time? If they really loved me, wouldn’t they be happy for me? And, above all: If they really understood me, wouldn’t they get that whatever thing they envy—the relationship, the career milestone, etc.—didn’t come to me easily: that I’m negotiating its compromises and complications, that I’m dying to talk about the hard parts of good things, too?

When we succumb to envy’s allure, we slot ourselves and others into narrow tropes. We refuse to see the entire story.

In the example of the Evil Queen, imagine if, instead of exiling her, Snow White’s stepmother took the time to get to know and actually speak to her stepdaughter—to see a person instead of a competition. The Queen was so committed to the story that most fed her self-righteous insecurities that she rejected her stepdaughter’s very humanity.

This need for complexity—for engaging in the fullness of people’s lives—is present for the “envied” person, as well. This is why a part of me has always been wary of, even as I’ve been (vainly) flattered by, the whole “they’re just jealous” rhetoric. Casting the person who envies you as simply bitter, or petty, or even pitiable misses the valid, deep-seated feelings behind their envy—feelings that likely have very little to do with you at all.

Sometimes envy is spurred by very real structural privileges, material disadvantages, and aspects of life that are as immutable as they are unfair. In those cases, how can a discussion of envy become a productive analysis of its particular contexts and impacts? In her book, Ugly Feelings, scholar Sianne Ngai argues that envy can actually be “a recognition of social and economic inequalities,” hence “our culture’s tendency is to stereotypically dismiss envy as a merely ‘feminine’ affect” and, therefore, as “trivial.” Envy can be a powerful mirror to and critique of access to power, privilege, and influence—no wonder its discredited and most associated with vain queens.

In the other scenario, in which the envious person believes that they can’t ever get the great job, partner, routine etc., how can you—as someone close to them—emphasize that they are worthy of those things? How might you dispel their envy-frenzied notion that having that one thing automatically expunges your other issues?

Envy, if both parties can get past their own guarded-ness, can be a space for joining, for expressing profound frustration, grief, want, or fear to someone you trust. You’re also not alone in the things you envy: After posting my prompts about envy and jealousy the other day (answers pictured below), I was stunned to realize that so many of the people I envy, or otherwise imagine as “ahead” of me in life, experience the exact same insecurities that I do.

So, here’s my proposition, to all of us, as we wade the waters of that green-eyed emotion we’re supposed to never feel: Let’s be more honest about not just our envies and where they come from, but the nuances of our lives. When we genuinely listen to and openly share those intricacies—and create space for pain, sweetness, difficulty, and difference within our experiences—it’s easier to turn the dial down on resentment and up on connection. Better yet, we might start to believe that many of the things we want, that our envy hungers for in its raw and keen way, we deserve to have—if only we can bravely speak them.

One Nightstand

I’m getting deeper in Demon Copperhead (it’s 550 pages!) and really starting to get immersed in Demon’s world. I’m also pretty excited about my TBR (I had some great scores at Half Price Books and a solid library haul recently). I’m planning to read Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation next. Has anyone else read it?

Ok gotta run to yoga! Thanks for reading <3

Love,

Jen

Love this! Naming and destigmatizing envy!